EQUAL VICTIMS

The Universal Reality of Intimate Partner Violence

INTIMATE partner violence (IPV) transcends boundaries of nationality, class, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. It's a widespread issue impacting relationships of all kinds.

While anyone can be a victim or perpetrator, navigating its complexities can be particularly challenging for marginalised communities.

This is where our research comes in. Lifeline Youth Empowerment Center partnered with 76 courageous individuals who shared their experiences through an innovative visual data collection method which was co-created with Data4Change, our community members, and health and IPV experts.

But before diving deeper, let's explore the broader context of IPV.

Intimate partner violence

ACCORDING to a 2018 study from the World Health Organisation (WHO), 27% of women globally (aged 15-49) have experienced IPV in their lifetime. That same year, the reported figure for Uganda was 45% (World Bank, 2018). A more recent study by the Ugandan Bureau of Statistics in 2021 shows that IPV levels have risen to 56%.

This means more than half of all women in Uganda have experienced IPV, making it highly likely that if you are Ugandan, you or someone you know has been affected.

Just as in heterosexual relationships, IPV is a serious concern within the LGBTQ+ community.

In 2023 the African LGBTQ+ community was rocked by the news that Edwin Chiloba, the Kenyan designer and LGBTQ+ activist, had been killed by his partner.

But how common is IPV in LGBTQ+ relationships?

Kenyan designer and LGBTQ+ activist Edwin Chiloba. Credit: Lawren Studios.

Kenyan designer and LGBTQ+ activist Edwin Chiloba. Credit: Lawren Studios.

The LGBTQ+ data gap

NEITHER WHO or the Uganda Bureau of Statistics collect data on the prevalence of IPV amongst the LGBTQ+ communities.

In fact, when it comes to IPV and LGBTQ+ relationships, there is a massive data gap both globally and here in Uganda.

This data gap has real life consequences for a group that is already marginalised and discriminated against.

Not only does it mean that physical and mental healthcare providers are unable to adequately plan and provide care for LGBTQ+ victims of IPV but it also has a more sinister effect.

The data gap contributes to a lack of understanding and compassion, or at worst a denial, of the existence and prevalence of IPV in LGBTQ+ relationships amongst the LGBTQ community itself.

Filling the data gap

OUR new research aims to fill a small part of this data gap.

In 2023, we conducted a survey with 76 Ugandans from the gay, bisexual, or queer (GBQ) community to explore their experiences with intimate partner violence (IPV).

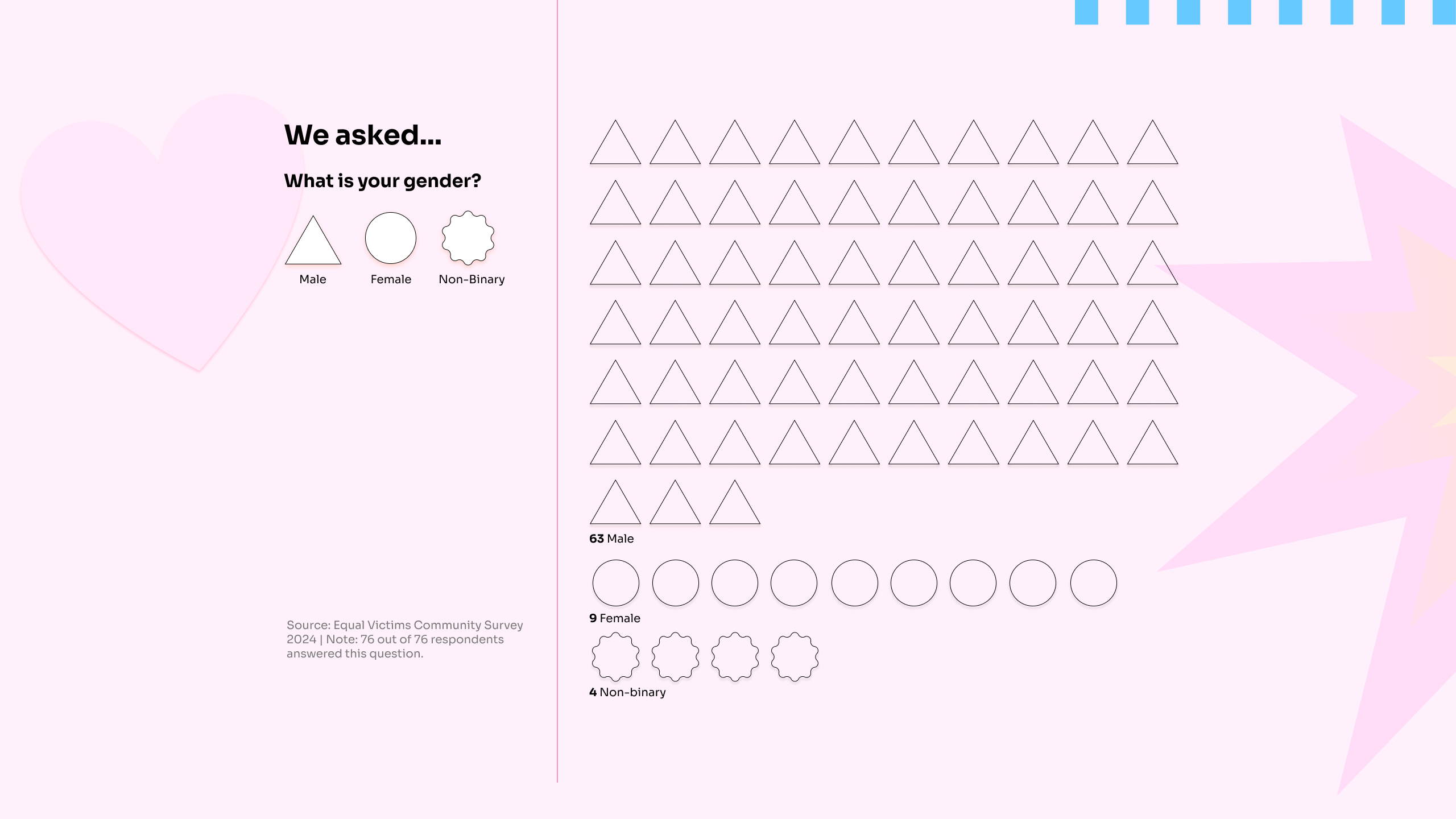

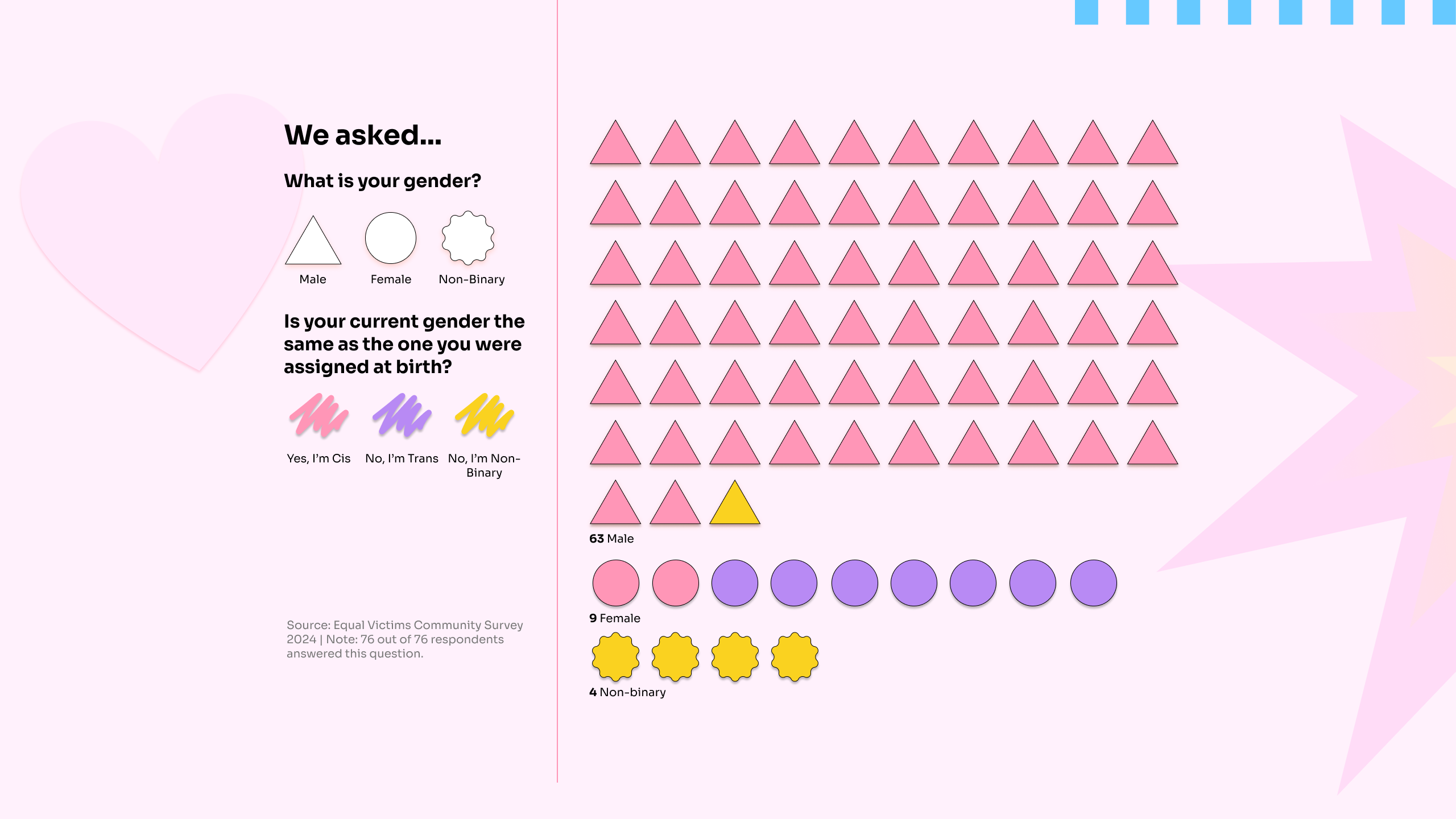

Our participants provided insights into their gender identities, pronoun preferences, and how they identify within the LGBTQ+ spectrum, revealing a tapestry of diverse personal identities.

Out of the 76 respondents, 63 identified as Male, 9 as Female, and 4 as Non-binary.

We asked whether their current gender identity aligns with the gender they were assigned at birth.

56 of the males answered "Yes, I'm Cis", indicating their gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth.

Among the females, two identified as cisgender, while seven identified as transgender, marking a transition from the sex assigned at birth.

The non-binary respondents all embrace identities that differ from those assigned at birth.

The pronoun preferences of our participants add a vital layer of insight into how our community expresses and affirms their gender identities.

The majority of those identifying as male use 'He/him' pronouns. 'She/her' is exclusively used by those identifying as transgender females, and 'They/them' is unanimous among our non-binary community members.

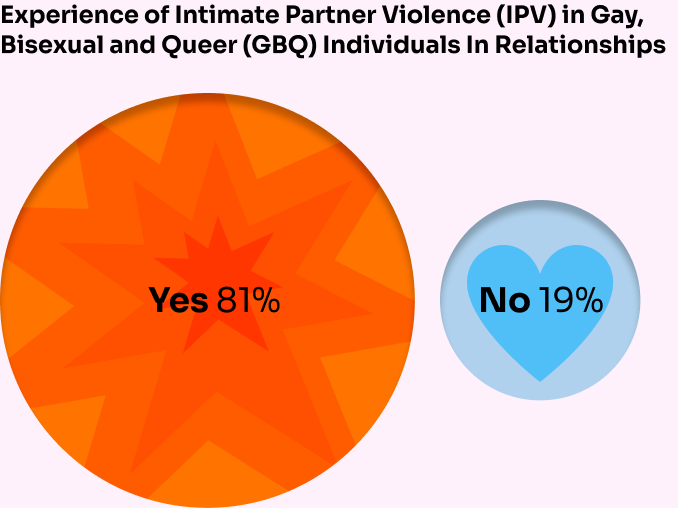

THE results from our research are concerning. 81% of the individuals surveyed who are, or have been, in a GBQ relationship said they have experienced IPV. This is significantly higher than that of heterosexual cisgender women in Uganda.

Types of violence

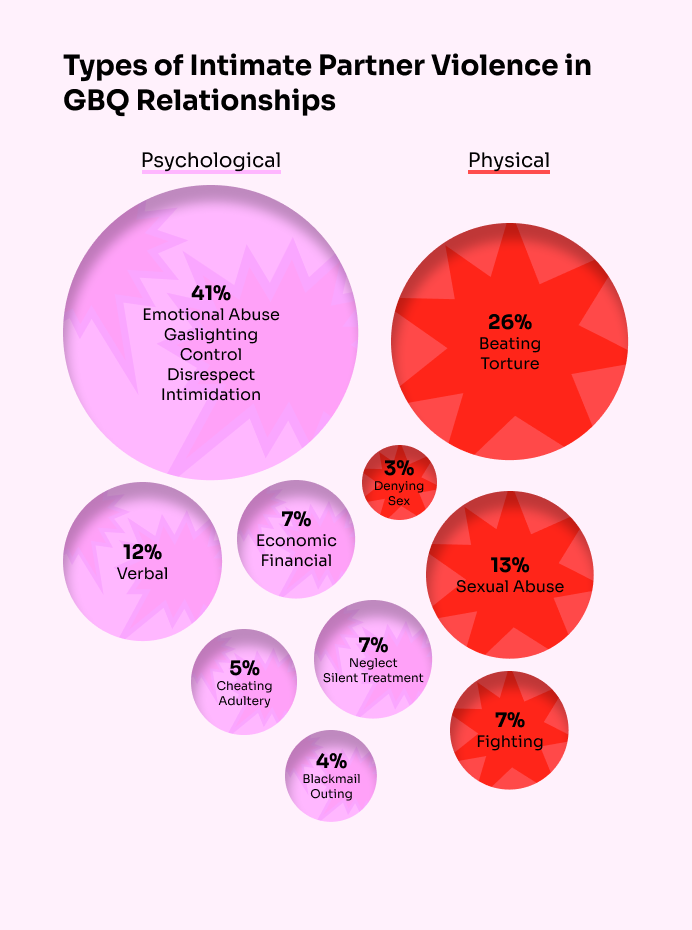

JUST like in cisgender heterosexual relationships, IPV in GBQ relationships can take many shapes and forms. It can be psychological or physical and sometimes both at the same time.

The recent National Survey on Violence Against Women and Girls by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics breaks down the types of violence into three categories.

This data highlights the violence cisgender Ugandan women have faced from male partners, but there is no official data on IPV in LGBTQ+ relationships in Uganda.

Our community survey found that 41% of GBQ respondents experienced emotional and psychological abuse, including gaslighting, control, disrespect, and intimidation.

Physical abuse, such as beating and torture, was reported by 26%. Other forms of abuse included sexual abuse (13%), verbal abuse (12%), and neglect and economic abuse (7%).

Excuses, excuses...

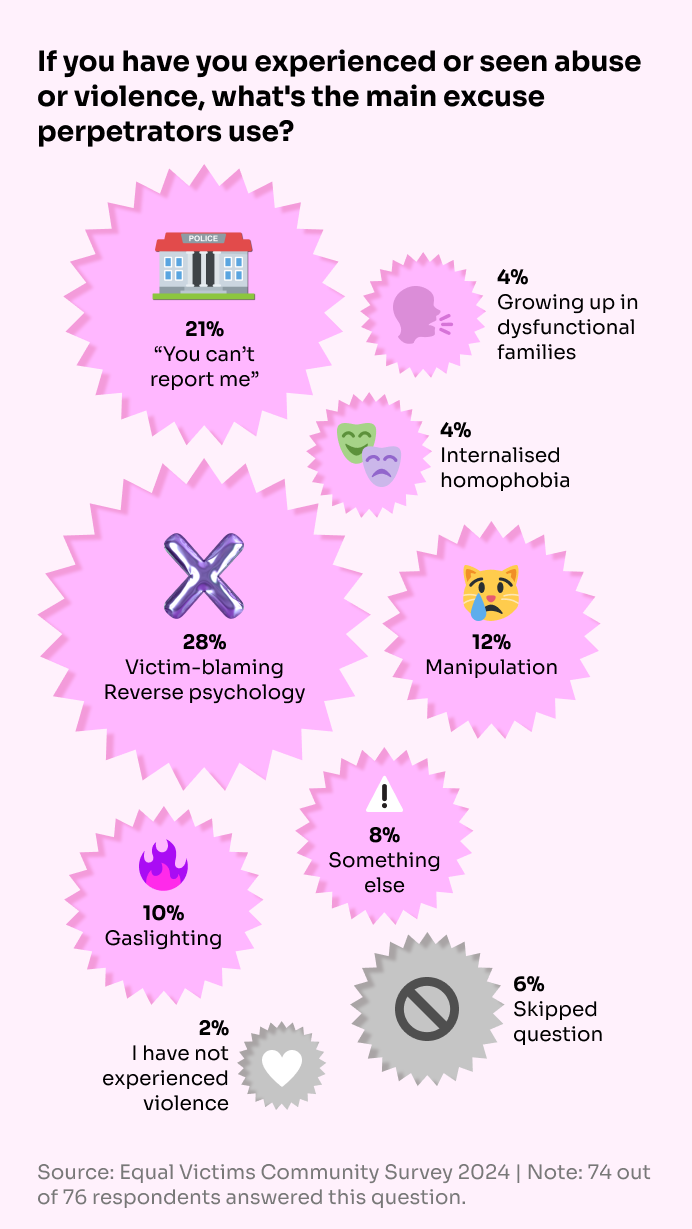

OUR research shows many similarities between IPV in heterosexual and GBQ relationships. The most common excuse that perpetrators of IPV in GBQ relationships use to justify their violence is ‘You made me do this’, echoing IPV research focusing on heterosexual relationships.

But the excuse ‘You can’t report me anywhere’, is sadly more true for Ugandan LGBTQ+ people who have a violent or abusive partner.

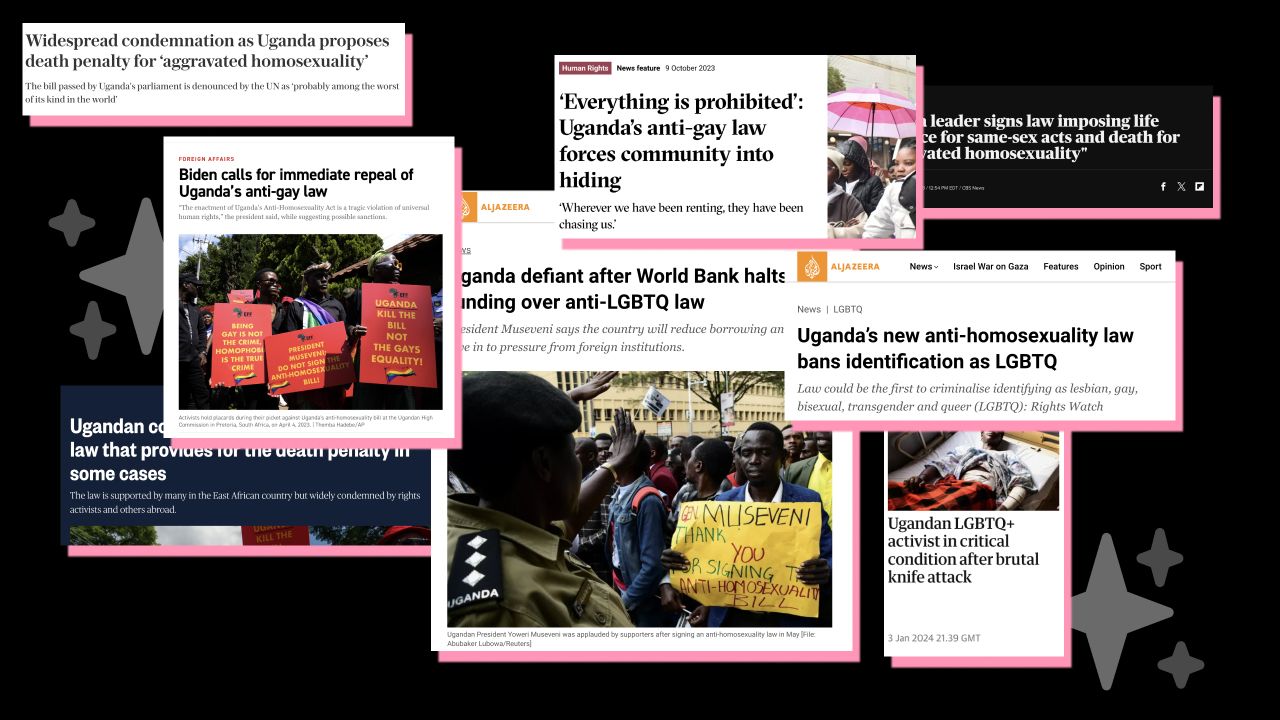

Institutional homophobia and Uganda’s new Anti-Homosexuality Act (2023) has led to an absence of proper reporting channels.

This lack of support from the state leaves a significant portion of the community vulnerable, and perpetrators of harm feel emboldened knowing they can act with impunity.

Our project aims to address these systemic failures and empower individuals within the queer community who are experiencing IPV by providing avenues for recourse and protection. You can find these links at the end of this story.

Power dynamics and imbalances

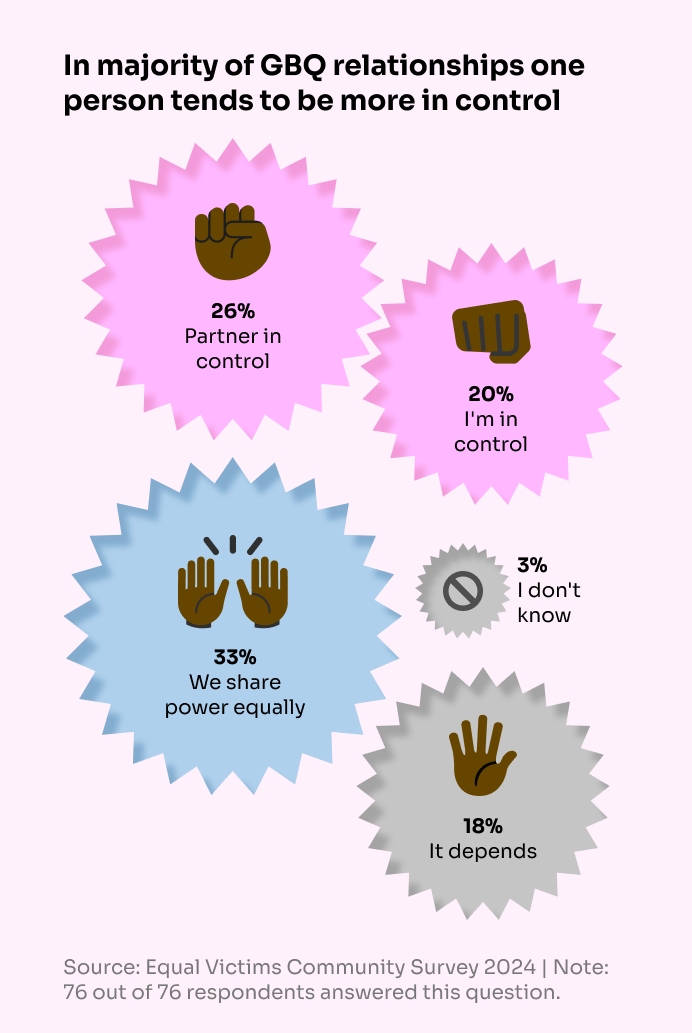

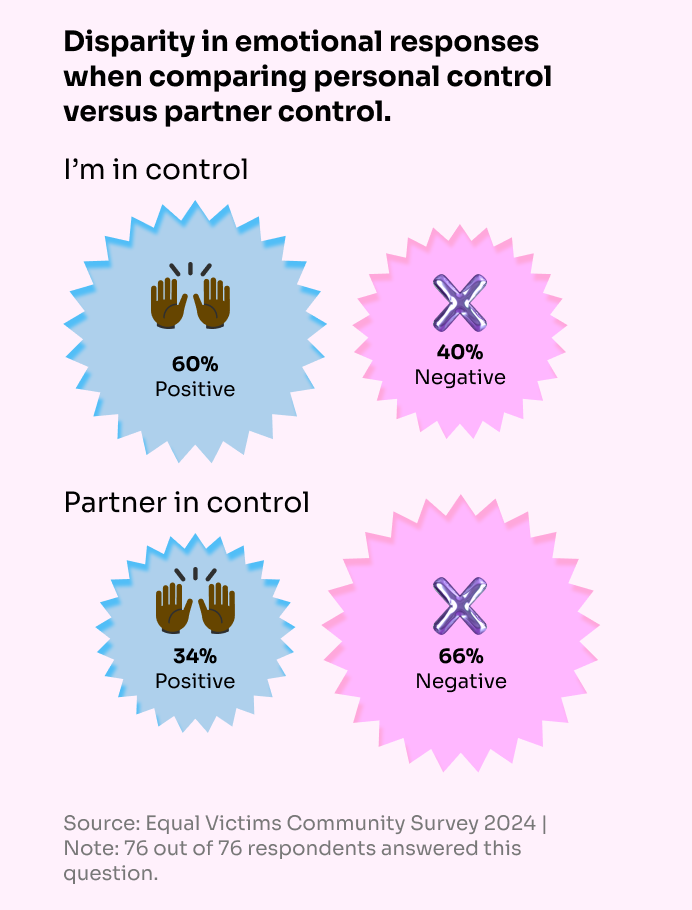

OUR research shows that power is shared equally in GBQ relationships only 33% of the time.

Unsurprisingly, in relationships where the respondent is not in control, they feel negative emotions. In relationships where there is more equal power sharing, or where the respondent is the one in control, they feel more positive feelings about the relationship.

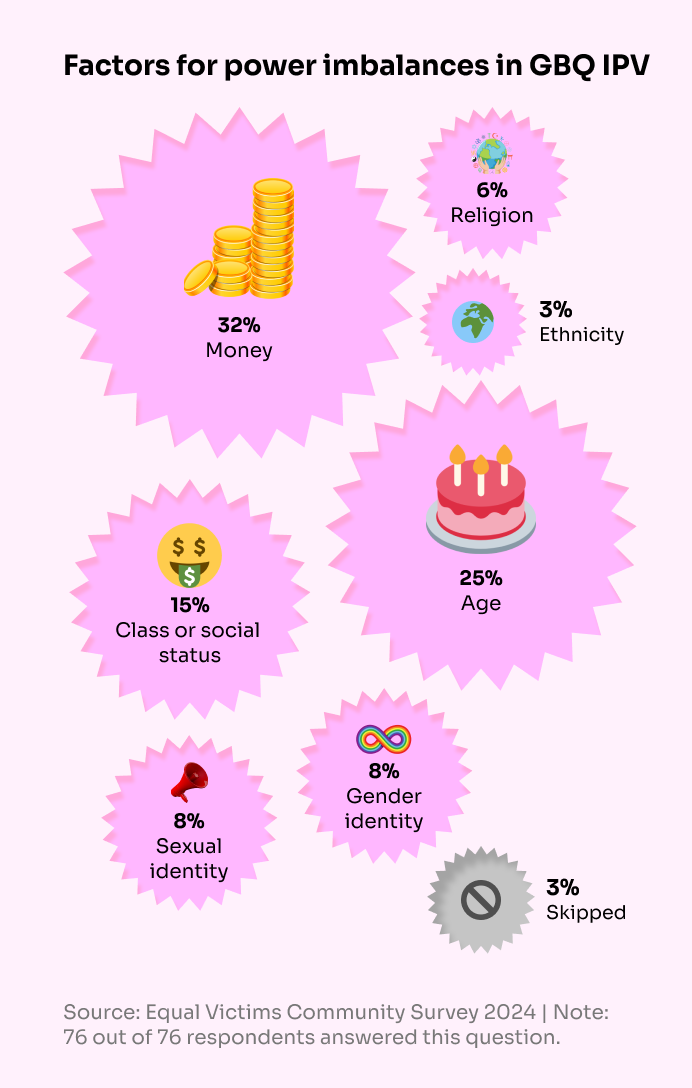

When it comes to power dynamics and how this affects IPV directly, there are some similarities between heterosexual and GBQ relationships.

Power imbalances such as wealth, age and class are things that affect both groups, but our research also shows that GBQ relationships have their own unique and complex power dynamics, often compounded by external factors such as anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination, internalised homophobia and misogynistic attitudes to sexual roles and gender identities.

Public attitudes

DESPITE domestic violence having been a crime in Uganda since 2010, most Ugandans still believe it is a private rather than a criminal matter.

An Afrobarometer report from 2023 highlights gender disparities in views on domestic violence in Uganda. 62% of Ugandans overall consider it a private matter, but this view is held by 69% of men compared to 54% of women.

The same Afrobarometer study delved into public perceptions about the potential community backlash against a woman reporting her husband for abuse in Uganda.

It found that a majority, 54% of Ugandans, believe that such a woman would likely face criticism, harassment, or shaming. This indicates that victim-blaming is a widespread problem, particularly pronounced in Central Uganda.

After the Ugandan government introduced one of the harshest anti-LGBTQ+ legislations in Africa in 2023, the situation for LGBTQ+ victims of IPV worsened, making it even harder for victims to speak up.

If an LGBTQ+ relationship is considered a crime by the authorities, how can one report being a victim of abuse in such a relationship to those same authorities?

The risk of being arrested just for being LGBTQ+ means perpetrators of IPV in LGBTQ+ communities are now more likely than ever to escape any repercussions.

Fears of naming and reporting perpetrators

THE apprehension surrounding the identification and reporting of abusers is palpable. Our research into IPV in GBQ relationships highlights that abuse is common.

When asked if they have experienced abuse and violence in their own relationships, 79% (60 respondents) said yes, they had, either in a relationship at the moment or in the past.

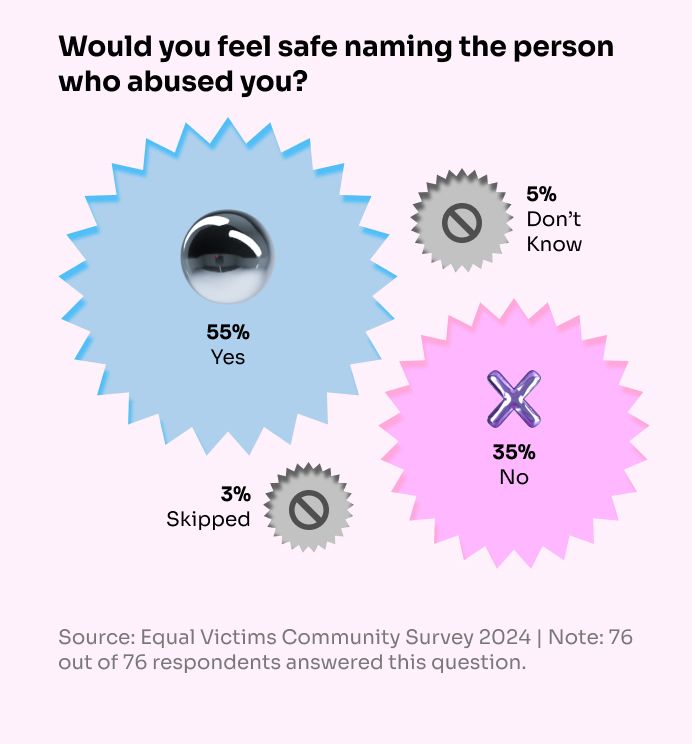

OUR research further shows that despite the potential consequences of sharing their experience of IPV with someone 55% (42 out of 76) would feel safe naming their abuser.

When it comes to naming their perpetrator, individuals overwhelmingly trust their friends, with 80% (57 of 71 respondents) feeling safe to share with them.

On the other hand, family and police are the least trusted. Only 3 out of 57 respondents said they felt safe confiding in family members, and even fewer, 3 out of 61 respondents, felt safe turning to the police.

This stark contrast highlights a critical issue in perceived safety and support from these groups who should provide trust and support, and underscores the need for better support systems within families and law enforcement to provide a safe space for individuals to come forward.

It is here at the reporting stage where the data between heterosexual and GBQ experiences of IPV most differ.

Comparing data from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics with our findings, cisgender heterosexual women are substantially more likely to disclose abuse to their families (62% vs. 5% of GBQ men).

This highlights a stark contrast in reporting behaviours between heterosexual women and their LGBTQ+ counterparts.

Conviction rates

IN 2023 a total of 14,681 cases of domestic violence were reported to the police in Uganda.

According to the Uganda Police Force Annual Crime Report from 2023, only 1,520 cases made it to court, and out of those only 423 secured convictions (25 cases were acquitted, 183 cases were dismissed while 889 cases are still pending).

LGBTQ+ people in Uganda are even more unlikely to report IPV to the police than their heterosexual counterparts, due to the risk of being ridiculed, shamed, physically abused, or arrested.

There is no data available on the conviction rates of domestic violence in LGBTQ+ relationships. State-sanctioned discrimination leaves the LGBTQ+ community vulnerable, and perpetrators of IPV feel emboldened knowing they can get away with it.

We hope that our project will help to address these systemic failures and empower those within the queer community experiencing IPV by providing avenues for recourse and protection.

What to do next?

OUR report has shown that IPV is an issue that both heterosexual and LGBTQ+ Ugandans face. IPV, unlike the law, does not discriminate; it is a common problem we all face and a common problem we can all help to address.

Are you or someone you know experiencing IPV?

You are not alone. Here is advice on what you can do next and who can help you.

Are you a health or mental health professional?

Tips on how you can treat and engage with LGBTQ+ patients experiencing IPV.

Are you a legal professional?

Advice on how you can engage with LGBTQ+ clients experiencing IPV and discrimination.

Are you interested in this issue?

Information for researchers, journalists, NGOs, on IPV in LGBTQ+ communities.

More about our research

CONDUCTING data collection about IPV in the LGBTQ+ community in Uganda, which recently introduced some of the harshest anti-LGBTQ+ legislations in the world, was not easy. There are the obvious security risks that come with collecting data from a targeted marginalised group but there are also other types of risks, such as the possibility of re-traumatising survey respondents who have experienced physical, sexual and psychological abuse in relationships, and the need to establish trust between the surveyors and the respondents.

To address these issues Lifeline Youth Empowerment Center, Ugandan LGBTQ+ healthcare providers, Ugandan LGBTQ+ victims of IPV, psychologists specialising in trauma and domestic violence, and Data4Change co-created an innovative data collection method. The survey was administered by Ugandan LGBTQ+ community members.

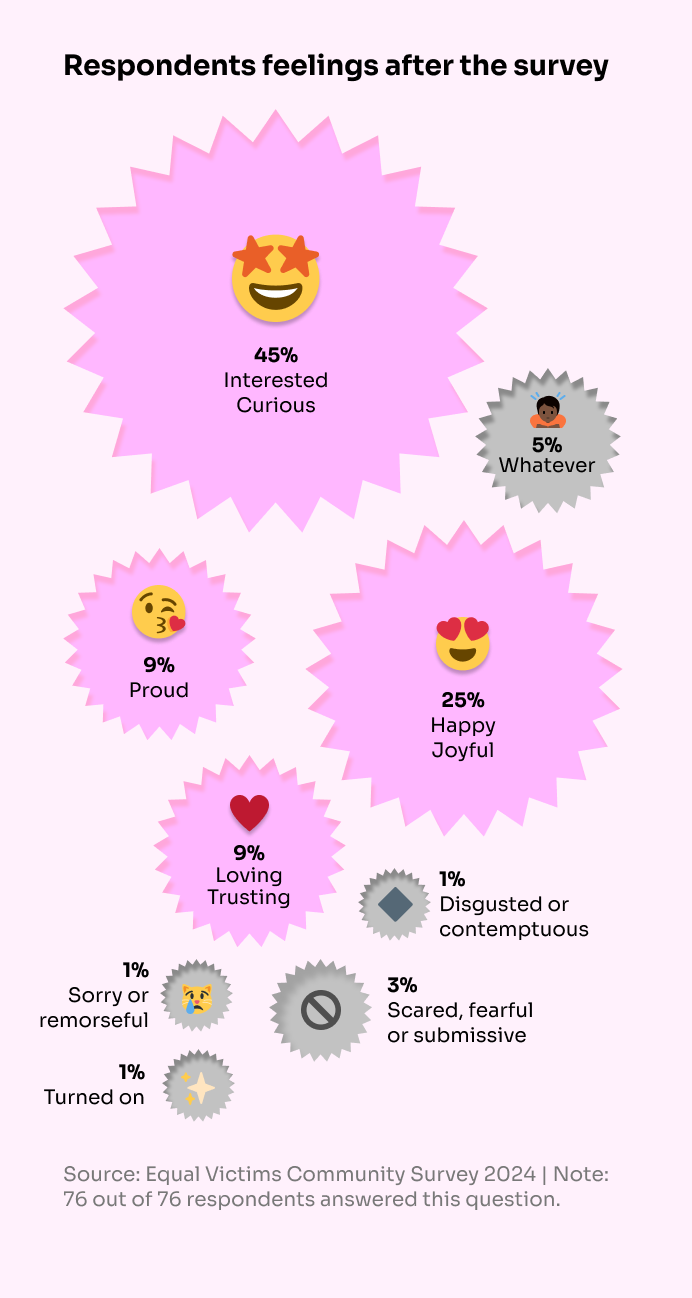

The data collection methodology integrated art into its design to give the respondents non-verbal tools to articulate their experiences. At the end of our data collection activity the majority of respondents reported feeling curious, happy, trusting and proud of having completed the survey. That to us is a good end result.

This is a project by Lifeline Youth Empowerment Center in collaboration with Data4Change.